[Photo credit: Joy Lai, State Library of New South Wales. Images courtesy of Cathy Perkins, Joy Lai, Monash University Publishing and the State Library of New South Wales.]

The editor as historian: Cathy Perkins

Transcribed and edited by Dr Catherine Heath AE and Dr Pam Faulks AE

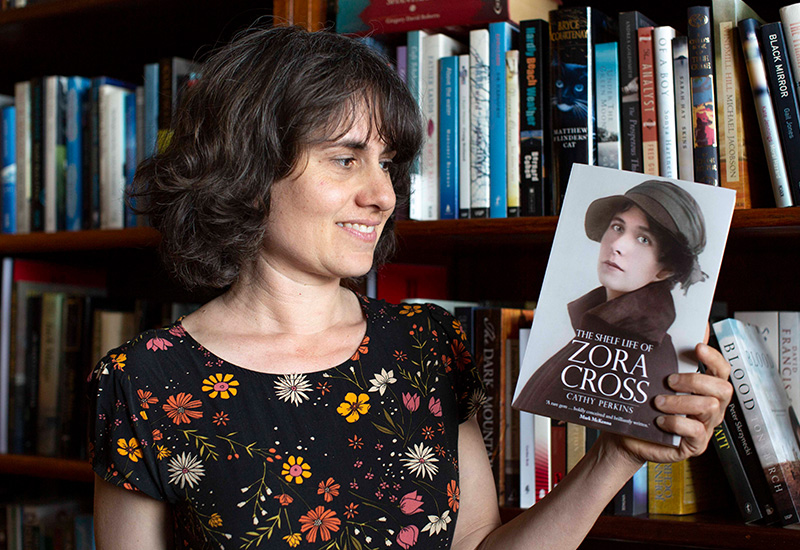

At the Editors NSW June 2020 meeting, author and editor Cathy Perkins talked about her editorial work at the State Library of New South Wales (SLNSW), which led to years of historical research for her new biography, The Shelf Life of Zora Cross (Monash University Publishing, 2019). She discussed accessing original documents in the library’s collection and how her background as an editor influenced her process of researching and writing the book.

Cathy Perkins edits the award-winning SL (State Library) Magazine, other publications, and exhibition text at the SLNSW, having previously worked as an editor for academic and trade publishers.

I am going to talk about my life as an editor: the 20 years of my career as an editor and my work at the SLNSW. Then, look at why I decided to write a biography of the little-known writer Zora Cross, how I went about the research and writing the book, through the perspective of me as an editor doing that research and writing.

Becoming an editor

To start with, I am going to take you very briefly through the past 20 or so years of my involvement in books, publishing and now a library.

In the mid-1990s I finished an honours degree in English literature, having dropped out of a law degree. It had taken me a while to finish this honours degree and I wondered what I was going to do for a job.

The job I ended up getting was as a bookseller at my local Dymocks. Working in that bookshop made me appreciate how books are packaged and marketed to readers, and I decided that I wanted to stay in the book industry.

So I spent time applying for jobs in publishing companies and eventually, after six months, I got a job as a publisher’s assistant at UNSW Press. There I was working with the submissions that came in from authors and with the managing editor and the sales team, so everyone involved in that life cycle of the book. I began to love it even more, the way that a book went from a vague idea of an author or a publisher through to the discussions — often very heated, sometimes even angry discussions — in the publishing company; and then the editing, the design, the marketing and the publicity, and the response from readers. Going through that cycle with each book was fascinating to me.

My next job, after a couple of years at UNSW Press, was for a literary agency, where the focus was on relationships between writers and publishers. I began to get a sense of the alchemy that is involved in creating a book and the collaborative process involved in getting a book from a rough idea over drinks in the agent’s office to a finished book — sometimes manuscripts that you think will never work, seeing them going through that collaborative process in the publishing company, and with the agent’s input as well, to become a successful book.

I would help review the submissions that came into the agency every week and give feedback on manuscripts before they were pitched to publishers, so that is where I started doing a bit of editorial work. I had done some at UNSW Press, but more reports on manuscripts than hands-on copyediting. At the agency I would help with some pitches to publishers as well. In 2000 I represented the agency at the Frankfurt Book Fair, which was an amazing experience, but I have not been back since.

While sitting around in the agent’s office, I was fascinated by the archive of letters in the storeroom that was a record of relationships between the agent, the author and the publisher, and all the emotions and politics involved in producing books. I was especially interested in the record of books that never came to be, or that struggled to find a publisher — the letters surrounding such books, and all the opinions, the way that the industry and the relationships were. It was a business, but it was also quite intimate in the dealings that people had with each other.

During this time at the agency, I figured out that the role that suited me best in publishing was to work as an editor. It suited my personality and the love of close reading I had developed through studying English in my university degree and even before that at school.

After a year and a half with the agency I was lucky to get a position as an editor at the trade publishing house Pan Macmillan, where I worked on books that went from a very rough and raw manuscript to a polished work that sold in the tens of thousands.

There were four or five in-house editors there at Pan Macmillan, and we would project-manage books and send them out to freelance editors and proofreaders for a range of flat fees. We would usually also have one book on the go that we would copyedit ourselves. We would mark up the hardcopy manuscript in pencil before it was sent to the typesetter to create the pages, and we would have to do it very neatly so that the typesetter could decipher all those markings. I had done a short course in editing while I was at UNSW Press but I mainly taught myself to edit on the job there, with the help of copyediting manuals I read on the weekend and at night, and by spending long days — hours and hours — editing books. I also enjoyed the other sides of project-managing books as well: dealing with the author, getting the images together and doing a photo shoot for the cover.

I was quite addicted to the book industry by then and I felt that, at 29 years old, I had my dream job. But after only a few months at the company I realised I was pregnant and I was told I had not been there long enough to qualify for maternity leave, so I had to leave. I had my daughter and I did some freelance work for Pan Macmillan when she was a baby. My great trade publishing ambitions came to an end there, but this was all going to connect to writing the book that focuses on a lot of publishing history, so it fed into that.

When my daughter was one, I got a part-time job for the legal publishing company LexisNexis (which had recently changed its name from Butterworths). I rarely meet an editor who has not done a stint at a legal publishing company and this was where I really consolidated my editorial skills, working in a team of about 10 editors on legal newsletters. As well as the in-house training, all my work was checked by another editor and the Managing Editor, so that process over the few years there really helped, feeling like you were in an editorial factory, in a way, that that was all you were focusing on and the camaraderie of working with other editors was great as well; it was a great apprenticeship. We would work on hard copy with a blue and a red biro sticky-taped together to make our proofing marks; so we would do the markup of the letter in blue and then the proofing mark in red, and keep swivelling these red and blue pens around all day. We also used hard copy sources mainly, though some online also, to fact check.

During my three years with LexisNexis I had my son, and when my kids were one and three, I got a new job as Communications Officer for the Australian Society of Authors (ASA). After a year there I saw a job ad in the newspaper for an Editorial and Exhibitions Officer at the SLNSW. I applied, got the job, and have worked there now for nearly 14 years.

The State Library

The job at the State Library was initially half editorial and half desktop publishing, but I was eventually allowed to focus solely on editing work (mainly because there were lots of other people working there who were much better at graphic design and they needed the editorial support); so that was good, shaping the job to suit what I wanted to do.

Over the years at the State Library I have edited the staff newsletter, the members’ magazine, annual reports, exhibition text, gallery guides, brochures, advertisements, signage, website copy, and even the signs for the toilets. Everything goes through me for an approval process, so we will have discussions on whether a baby-change sign should picture a woman changing a baby or a self-changing baby, and there is a lot of working really closely with the graphic designers there. Currently there is one other editor working with me at the library; in the team there are two editors and three graphic designers.

Working closely with the State Library’s three graphic designers has made me very aware of the visual impact of text and that collaboration between the editor and the designer when looking at things like font sizes, line breaks, the relationship between words and images. I have found that working in a cultural institution like that is a different kind of editing. I have also learned a lot about exhibition editing from working with the State Library’s curators and creative producers of exhibitions — particularly how conversational exhibition text has to be but also, ideally, how succinct, to not distract from the objects on display, and what an exhibition visitor does when they come into an exhibition gallery.

In 2018 the State Library renovated its galleries and opened new gallery spaces in what were previously staff and storage areas. Our most popular exhibition each year is World Press Photo, but we also produce many historical exhibitions using the State Library’s collection of books, manuscripts, paintings, photographs, objects, architectural plans and so on.

[Cathy referred to images of the State Library and its staff.]

The State Library consists of the Mitchell Library, the building that was built in 1910 and then added to, and the Macquarie Street building where the State Reference Library collection is.

There is a new paintings gallery where we used to have temporary exhibitions; a couple of years ago we put in a permanent exhibition of 300 paintings that had been in storage. Not everyone thinks of the State Library as having an art collection. Often the paintings were not collected because of their artistic or aesthetic merit but because they record something about the history of New South Wales, so it is a very interesting painting collection.

The card catalogues in the Mitchell Library Reading Room are mostly there for show but there were instances where [I used them in my research because] they had, say, a breakdown of manuscripts and I needed to look at the card catalogues to find out exactly which box the letters to a particular person were in; so they are not just for show and it is interesting that you still need to look in them. Whenever the State Library shares images like that [referring to an image of herself with the card catalogues in the Mitchell Library Reading Room] on social media they are really popular because that is the romantic view of the library and the romance of scholarship and the old building.

There are about 350 staff members at the State Library. Often you do not get a sense of that because you just see the people on the desk, but there are a lot of people cataloguing, digitising, and organising events and exhibitions and all of that. [In a staff photo of the State Library] here I am holding my book in the front row. It was taken the week before my book came out and we were all told to bring a book, so I got a colleague to hold my book but then they swapped it just before the photo was taken.

The kind of editing I do at the State Library varies a lot; so it might be just a proofing job where I am asked to look at something before it goes to production — ‘Can you run your eagle eye over this?’ — or it could be rewriting the text of a blog post drafted by a web developer, or someone who doesn’t think of themselves as a writer and who’s quite happy to have it rewritten so that it is a readable blog or magazine article, or it might be a curator who wants to review every mark-up that you make. There are a lot of different people you work with, mostly internal writers, and the amount of intervention really varies. I have learnt a lot about writing as well, partly through the kind of editing that I have done there.

About two years after starting at the State Library I became the editor of the library’s magazine for members, now called SL Magazine. This magazine comes out four times a year, with about 56 pages, and includes feature articles based on the State Library’s collections, new acquisitions, exhibitions, and fellowship research, as well as news and promotional highlights.

As the editor, I convene a committee for the magazine at the State Library to discuss the content. I commission articles from internal and external contributors (from internal writers but also from historians and other people using the collection). I edit the copy, organise photography with the State Library’s in-house photographers (both photos of people — the writers — and setting up arty shots of the objects, which we spend a lot of time doing and is very rewarding). I also do picture research for historical images. Then I brief the in-house graphic designer and oversee the design and approvals process, but the graphic designer is involved in all the production side of it.

Editing the magazine takes up about half my time at the State Library and it is a great pleasure because I work in collaboration with my colleagues to produce a publication that is very much appreciated by its readers. I also learn a lot about the State Library’s collection.

We print about 3,500 copies of SL Magazine and send out most to ‘Friends’ and supporters of the State Library, as well as to all public libraries in New South Wales.

[Cathy referred to images of an SL Magazine photo shoot]

As editor of the magazine I may be involved in setting up a photo shoot. For example, I worked with the photographer, Joy Lai, who is the main photographer at the State Library, for an article about our collection of Vietnamese posters. I had been to the Sydney Writers’ Festival and heard the writer Sheila Ngoc Pham speaking. I invited her to write about anything she wanted to in the collection and she chose this collection of posters. We wanted a really eye-catching portrait of her, so we got the posters out and we had to check the collection care [notes], that it was okay to use them in this way, and get the exhibition people to help with magnets to set up a kind of temporary exhibition. There is a final shot that we took of Sheila and the spread that the graphic designer created, and it was a lovely, really moving piece that she wrote, so I was really satisfied with that. You can see back issues of the magazine [PDFs] on our website. People do not necessarily know that we have the magazine because it mainly goes to Friends of the State Library.

While at the State Library I have formed a network of other editors who work at museums, galleries and libraries. It is an informal group that we call ‘Editors in Cultural Institutions’, with members from the State Libraries of New South Wales and Victoria, the National Library, and the major museums and galleries in Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane and the ACT. (Smaller and regional cultural institutions rarely employ in-house editors.)

We meet once or twice a year, and the different institutions take turns offering to host the group for a full-day seminar. We might go up to GOMA [Gallery of Modern Art] in Brisbane when the Asia-Pacific Triennial [of Contemporary Art] is on and we will take turns giving short presentations about the editing work we do, and there will be a lot of the kind of secret editors’ business that I am sure you talk about, all the trials and tribulations of being an editor and what we go through. It is really good to have that network and maintain it. We are also in touch informally outside it. Most of us work with only one or two other editors so we always have a huge amount to talk about when we get together. (There are many things only other editors understand.)

Research

It was not long after starting at the State Library that I was inspired to take on my own research project. I had settled into the job and thought it would be nice to have a research project of my own to think about. Before beginning this job, I had never done research using original documents like letters, diaries and photographs. I had done a small amount of research at the State Library for my honours thesis, but that was mainly using early 19th century printed journals: all I had really done was copy advertisements from old magazines. I had no idea about, or had never considered, the vast manuscript collections at the State Library until I became a staff member there.

I also had a sense of reading original archival material as something only serious scholars did — people with PhDs, for example — and that because I had not done a PhD that was somehow not accessible to me. I thought that you could only penetrate that kind of complex resource if you had enough prior knowledge. I also thought that I was not going to get the time to apply myself to it, working in an open-plan office.

But my job at the State Library brought me into contact with original material anyway, through the photography and through talking to other researchers. And I began to see that that material was no different from the letters in the literary agent’s storeroom. The State Library’s collections relating to the history of Australian publishing became very enticing to me.

This interest also satisfied that thwarted publishing career of mine. I should add that around this time I began reading a lot of literary memoirs and biographies, particularly biographies of editors and publishers such as the American Max Perkins (the great editor), the Australian Hilary McPhee and the English editor-turned-writer Diana Athill.

When reading biographies of authors, I particularly liked those that included the biographer’s process of discovery as part of the narrative — for example, Ian Hamilton’s In Search of J D Salinger, and Janet Malcolm’s books on Sylvia Plath and Anton Chekhov. I also loved Hazel Rowley’s biographies, especially those dual biographies that focused on the relationships of Simone de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre, and of Eleanor and Franklin Roosevelt. These are some of the biographies that inspired me.

I had in my mind that if I were going to write a book it would be a biography, but I had not published anything other than the writing I had done for work. I thought if I did write a biography it would have to be of an unknown figure, because I thought it was going to take me a long time and I did not have the confidence to contest the ground with a better or faster writer who was interested in the same subject matter, so I kept my mind open about who that figure might be.

Discovering Zora

In 2008, a couple of years after starting at the State Library, I had an opportunity to curate a small display on Australian publishing. The main item on display was a set of illustrations that the illustrator and publisher Sydney Ure Smith had produced for the publisher George Robertson, co-founder of Angus & Robertson (one of the leading publishing companies in Australia in the late 19th and early 20th century), when negotiating an advance for a book.

As part of my research I took the old wooden lift down to the Mitchell stack (where staff members like me are no longer allowed to venture on our own – it is now more tightly controlled than it was in 2008). I sat down on the concrete floor to check a reference in a book of letters to and from George Robertson.

In that book I came across a set of letters surrounding the publication in 1917 of a collection of poetry called Songs of Love and Life by the writer Zora Cross. I had never heard of the book or its author, and there were several things about these letters that hooked me.

One was the year 1917, and the fact that this book had been a literary success during the harrowing years of World War l. The book clearly focused on female sexual passion and it seemed interesting to me that Australians were buying a book of erotic sonnets at the same time as voting in the second conscription referendum on whether to send Australian citizens to war overseas. So it was a war story that I did not know about. At the time it was the lead-up to the World War I centenary and people were interested in what other stories there were to be told about that era.

There was clearly a story around the production of this book. George Robertson had initially turned down the manuscript without looking at it because of the mood he was in, and because Zora’s mother had offered to pay the printer’s bill, which was apparently ‘always a bad sign’. So Zora had self-funded a small edition published by Robertson’s former employee James Tyrrell. When Robertson came across an advance copy in the large bookshop that he ran in Castlereagh Street he was struck by Zora’s literary skill and flair so he immediately purchased the rights to publish a new edition. This was the kind of publishing story that I liked, of a book that people ignored and did not think was anything special but that was then discovered and became a big deal.

Robertson sent the poems to Norman Lindsay, the legendary artist who lived in the Blue Mountains, but Lindsay refused to illustrate the poems. He believed that women could not write love poetry because their ‘spinal column wasn’t connected to the productive apparatus’ — this was all in the collection of letters in this book — but Lindsay did produce a cover design because he wanted the commission money.

It was the success of the book in the face of Lindsay’s dismissal that drew my attention and the fact that this episode in publishing history, and Zora Cross as a literary figure, had been forgotten.

And it was also the character of Zora Cross. In a letter to George Robertson reproduced in that collection, she is effusive in her thanks and striking in her intimacy. She conveys all the excitement of an author about to be published by a ‘big publisher’, in a way that other authors are probably too polite to express, and she gives an insight into her life as a 27-year-old writer. She tells him how much she has suffered in the past, and that he should think of her as a child so that he can forgive the thoughtless things she might do.

It made me think about her suffering: What has happened to her? What is she going to do? What are these thoughtless things she might do, as though she was somehow out of control? As well as this pivotal episode of finding fame as a writer during the war and this exciting episode of the publication of the book, she was a subject that had a past and a future that I wanted to investigate.

The material

I started by looking up what had already been written about Zora Cross and found an intriguing entry in the Australian Dictionary of Biography by the literary scholar Dorothy Green. Here I learnt that Zora’s relationship with the Bulletin’s literary editor David McKee Wright scandalised Sydney’s literary world when David left his wife and four sons for Zora.

A few literary scholars and historians had written articles about Zora’s work, but there was not much scholarly writing about her. When I asked people if they had heard of her, some people would say they remembered reciting a poem of hers in primary school in the 1960s but most people had not heard of her.

The literary historian Michael Sharkey had written articles about Zora Cross, and had started writing her biography, and had done interviews in the late 1980s with family members who are no longer surviving, but eventually shifted his interest to David McKee Wright. His biography of McKee Wright, titled Apollo in George Street, was published in 2012. Michael Sharkey eventually gave me all his research material on Zora Cross.

I found Zora’s published work very interesting, especially Songs of Love and Life which, as well as the six erotic sonnets, included poems on subjects few writers would have touched, such as the experience of giving birth alone to a child born outside marriage. In addition to Songs of Love and Life she published another poetry collection, The Lilt of Life, two novels set in her home state of Queensland, several serial novels, and an abundance of journalism and poems — more ephemeral work — in newspapers, literary journals and magazines, much of it under pseudonyms. She also published the powerful Elegy on an Australian Schoolboy, written for her brother who died at the age of 19 in World War l, and her strong anti-war sentiment was unusual when the poem was published in 1921.

But I soon became even more interested in Zora Cross as a letter writer. Searching the State Library’s collection, I realised she had left behind more letters than many writers whose work better survived the scathing assessments of mid-20th century literary criticism.

She wrote hundreds of letters and most of them were in the State Library’s collection: bulging folders of letters to George Robertson, to the poet and literature professor John Le Gay Brereton, and the critic Bertram Stevens; many letters to Mary Gilmore and to George Robertson’s assistant Rebecca Wiley. These letters were very personal, and conveyed Zora’s personality and struggles as a writer. What really came through to me was her voice, a distinctive way of seeing the world with humour and insight.

There were also 21 boxes of Zora’s personal papers at the Fisher Library at Sydney University that had been in the family for a long time and became a bit fire-damaged and insect-damaged but eventually found their way to the University of Sydney, including drafts of the three novels about ancient Rome that she spent the later part of her life trying to get right. Only one would be published, as a serial, in the Sydney Morning Herald in 1933.

This collection at the Fisher Library is very different from the State Library material because it has not been sorted in the same way, with letters and photographs filed separately and ‘trivial material’ thrown out. It was a much less sanitised collection than the material at the State Library. So, alongside her university notebooks and letters from her son during World War ll, you will get boxes that have a nameplate for her house, some dried leaves in a paper bag, Mother’s Day cards, a copy of TV Week from the 1960s with programs marked to watch — it is more like the kinds of materials you could imagine in a writer’s house when they died — and lots of family letters as well.

There is also a great deal of material about Zora Cross online, both through the State Library catalogue and the National Library’s Trove website. Since I did this research, the Angus & Robertson collection has been digitised and Zora’s letters to George Robertson can be read online through the State Library’s catalogue. Other letters are still only available in hard copy, and you must register for a Special Collections library card, fill out a stack slip, and wait for the boxes to arrive for you in the reading room.

A really unusual thing about Zora Cross as a biography subject is that I had access to a detailed record of her childhood in her own words. From the age of nine to 20 Zora had dozens of letters published on the children’s page of the Town and Country Journal. (This newspaper was digitised and available through Trove.) This ‘Children’s Corner’ was edited by the famous children’s author Ethel Turner, so this was evidence not only of Zora’s childhood in rural Queensland and then Sydney, and her development from a quite well-behaved little schoolgirl to a slightly wild teenager, but it was also a record of her relationship with a leading literary figure of the time. That is why I went on to build the book based on these relationships that she had with people in the publishing industry.

Having so much material was really what kept me hooked and made me think I would never find a better biography subject than Zora Cross.

[Cathy referred to images concerning her research on Zora Cross.]

Photographic materials relating to Zora Cross include a publicity photograph that she had taken in 1919, and it is interesting because the day was 18 May 1919, her 29th birthday, but it was also three days after the pandemic restrictions for the Spanish flu in New South Wales were lifted, so she had rushed out to have this professional photograph taken and it is a nice parallel with today.

Zora worked as a vaudeville actress in Queensland — also as the editor of a small arts newspaper there and as an elocution teacher during World War l — and there is a rare photograph, from her family, of her in her vaudeville make-up.

Some of the research I did through Trove. The letters that Zora wrote to the Town and Country Journal are all digitised and on Trove, so I could search for them. I called up the physical newspaper and it crumbled in my hand, so it was fantastic that I could read her words in this way, and there’s lots of other personal material about her that can be found through the Trove website. It is almost like today’s social media, the way the children wrote to each other in this children’s page and referenced each other in their letters.

My selections for a publicity photograph that I was having done indicate the types of materials the State Library holds on Zora Cross: I got some of the material out and it shows an archive box of the Angus & Robertson letters and some other letters that were bound into a volume, but also the original Norman Lindsay cover for the book. So you can see the original watercolour that Lindsay made and then the way it was set out on the book cover, and then there is another wraparound cover that was especially for the press edition, which extracted quotes about the first, self-published, edition. That was quite interesting to see; something I was really interested in was the way books were marketed and produced at that time.

Writing

So I had all this material, a strong fascination for my subject and not much of a track record in writing, in completing a project of this scale. I was also busy, with a four-day-a-week job, a long commute, and children in late primary school. I tried sitting down to write the book on my day off and on the weekends but there was always something more important I should be doing, so it was hard to do.

I noticed that the University of Sydney had a biography subject in its coursework Master of Arts degree, run through the history department. So I enrolled in that to start with and eventually changed to a research master’s, supervised by historian Mark McKenna.

Being enrolled in the master’s meant I had to produce some writing at reasonably regular intervals. I could not just do all the research and then start writing after that. I had no real idea how to start. I thought I had to write a chronological biography; to write about Zora’s childhood, for example, I would have to go through all the material to look at and note down all references to her early life, do some family history research, come to grips with Queensland in the early 20th century, and then pull together a chapter about her childhood with all the historical context of what was happening in Queensland and in the world.

Not only was this very difficult to do — it seemed impossible with the time I had — but when I started writing in this chronological way, there was a kind of deadness to the writing. As far as the historical context was concerned, I did not feel I had anything to add that the reader did not already know: settlers like Zora’s family had a complex relationship with the traditional Aboriginal owners of the land, education for girls was quite a new thing at the time, and so on.

So I came up with a way of doing it where I would base each chapter on a discrete set of sources. I decided to write a first chapter about the letters Zora had written to Ethel Turner’s ‘Children’s Corner’. Not only was it more manageable to focus on this one set of sources, it also helped the reader to see Zora through Ethel Turner’s eyes. I planned to fill in the story of her childhood later when I had got through more of the sources.

So I kept writing chapters based on a discrete set of sources about her relationships with different literary figures: the critic Bertram Stevens, George Robertson, Norman Lindsay, Mary Gilmore and so on.

One method I used to keep going was to write first and research later. So I would start the day ‘free writing’ for an hour or so, based on what I remembered from the previous day’s research; then, when I had had enough of that, I would do more letter reading and note taking.

I wrote a set of about eight chapters about these different relationships, which was much more than I needed for a master’s thesis, and to start with, in the initial draft, they overlapped chronologically quite a bit. Then I took four of those chapters, added an academic argument and made that into the thesis.

Even though I wrote so much of this book as a research thesis, I still had a lot of freedom in how I wrote it. There was some pressure from the department — not from my supervisor — to write in a more academic way, in a dialogue with other scholars, rather than the more narrative-driven and experimental way I was developing, for example, switching between past and present tense.

So after the thesis I had a bit of a strange manuscript to try and get published. It focused maybe a little too much on the sources, and told Zora’s life in an incremental, sometimes oblique, way. I got some feedback that it needed to focus on Zora more than on the other characters, that it was too close to the sources, that the non-linear chronology was a bit of a problem, and even that my focus on my own perspective as the archivist or the biographer was not necessary, that the story was interesting enough in itself.

I eventually had an offer to publish it from Monash University Publishing with a year to revise and deliver the final manuscript. Having a contract completely changed how I viewed the book. I had to do what I could within the time limit and the word limit of 80,000 words. That was when I really went into a frenzy of work and imagined the reader buying this book. I felt a duty to the reader who might purchase it to give them a satisfying read. I also felt this was the one opportunity to make the story of Zora’s life better known and I wanted it to be as full as possible a telling of that life.

Part of me wanted to throw the manuscript out. I thought about going back and starting again but there were things I liked about the structure I had chosen. I thought each of these relationships had a tension to it and showed a different side to Zora’s character, while the better-known characters led the reader into the story of a lesser-known one. It also limited the biography’s cast of characters in a way that was easier for a reader to follow by focusing on a microcosm of her life.

I did a lot of work separating out the chronology so that, where things overlapped, I chose which episode belonged in a different chapter. I did a lot more research on Zora’s later life that I had not covered as much, so it told the full story of her life.

For example, I had already had some contact with Zora’s family, but had not really incorporated their reflections into the manuscript. I had contacted Zora’s daughter, April, when I read about her in Michael Sharkey’s biography of David McKee Wright. April was 88 when I first met her in 2012 and she encouraged me to finally do justice to her mother’s story. After I submitted the thesis, April wrote a 50-page manuscript memoir of her mother that she titled, What Zora Said, and I was able to incorporate a lot of her recollections into the revised draft.

I read a lot more sources and put together a reasonably full narrative of Zora’s life, which I could weave through the structure of these relationships. Reading the chapters again I felt that a reader could tolerate some overlap and some playing about with the sequence of events, but they also needed a chronological pull to carry them along, [one] that kept them wanting to find out what happened to her. So where, for example, the George Robertson and Rebecca Wiley chapters covered the same events from different perspectives, I moved the material from one to the other so that one covered an earlier period.

When I was submitting the manuscript to publishers, I had received some feedback that I should not insert my own authorial voice into the story, putting myself into the narrative. This is also famously one of David Marr’s key rules of biography: Do not put yourself in there and do not write about your research process. I listened to a podcast where he said that no-one wants to hear about you in the library doing your research, and I would tell people ‘Oh no, I have done that’, but they’d say, ‘It is okay; you work in the library so it is a bit of a different story’.

I decided that I could break this rule, especially since many of the biographies I liked best included the biographer’s experience of discovery, written in the first person. But I could see that it had to be done very carefully; I could only do it so much. I could only be in there when I was leading the reader into the material, drawing them into the story, and conveying my own enthusiasm. I also felt justified in putting myself into the book because Zora did this herself; one of the things I most admired her for doing was writing a series of profiles of other women writers in the 1920s and 1930s that were published in the popular women’s magazine, the Australian Woman’s Mirror, and in those articles she puts herself in there. You hear about her journey on the train on the northern line to visit an author at home, and she does it just enough to draw you into the story but not overwhelm the interview with her own personality. Later, especially in chapters where her life became more complicated so that the story itself was more complex and had gained momentum, I needed to take myself out and disappear.

My background as an editor influenced this process of revising the manuscript because I tend to focus on the problems rather than decide that it is good enough, and I tend to look at text very closely at a sentence level and at the connections between paragraphs. I could see the need to engage a professional editor to advise me on it. I found working with a copyeditor, as the author, I appreciated having a professional, fresh look at the manuscript. I ended up really respecting her advice, especially with things that she suggested deleting because it showed my own internal workings too much, so I often had to ‘kill my darlings’ by deleting paragraphs or sections.

That year, revising the manuscript was the hardest thing I have ever done, but I have had feedback from readers that it does carry them along. I like to think it also leaves a lot of Zora’s life open to interpretation, so I have heard from people who have come to completely different conclusions about Zora’s life and work after reading the book. I learnt a lot about writing that I hope can feed into another book project when I undertake one.

[Cathy referred to images of her book launch.]

The Shelf Life of Zora Cross was launched in November 2019 in the reading room at the State Library — I was really lucky that it launched before all of the [COVID-19] lockdowns — and I did a few interviews in bookshops, which was a great thing to do. There is an Instagram book page that the library did, and the State Library helped promote the book in other ways quite a bit as well — that was fortunate timing.